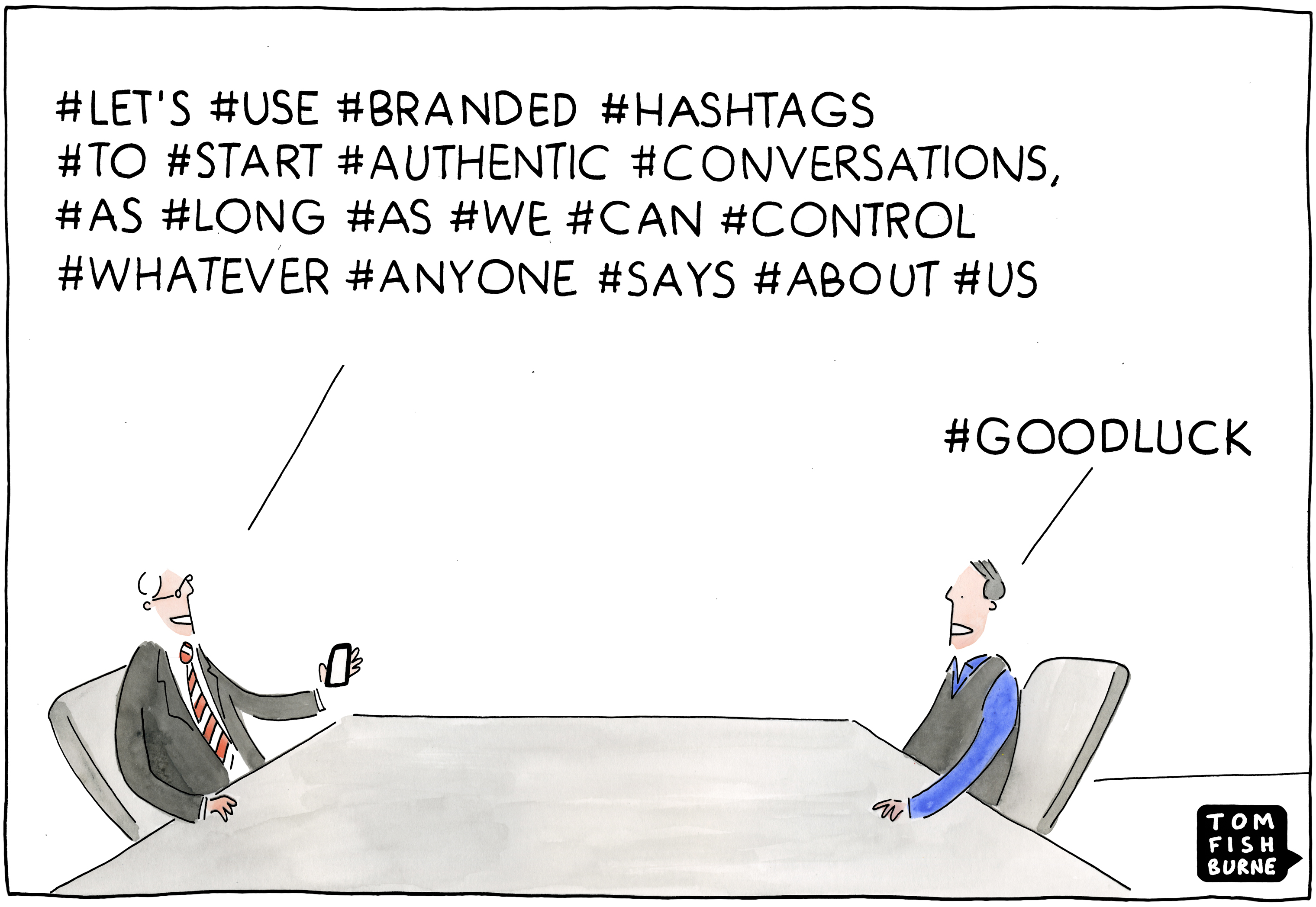

Social media allows brands to start conversations, but are the conversations worth starting?

Social media allows brands to start conversations, but are they conversations worth starting?

It seems like nearly every ad closes with an invitation to “join the conversation” with a dedicated Twitter hashtag. Beyond Twitter and Instagram, Facebook incorporated hashtags into its platform. Some marketers are referring to hashtags as the new URL.

But there’s a fundamental difference between hashtags and a URL. Brands aren’t in control of hashtags. JPMorgan Chase discovered this the hard way when it scheduled a live Twitter chat with the hashtag #AskJPM, inviting people to submit questions. The hashtag quickly started trending, but not for the reasons JPMorgan expected.

“Did you have a specific number of people’s lives you needed to ruin before you considered your business model a success? #AskJPM”

“If it came out Jamie Dimon had a propensity for eating Irish children, would you fire him? What if he’s still “a good earner”? #AskJPM”

“Is it the ability to throw anyone out of their home that drives you, or just the satisfaction that you know you COULD do it? #AskJPM”

It’s the same lesson that McDonalds famously discovered with #McDStories (which quickly devolved into snarky comments about Type 2 Diabetes and how McNuggets are made). When consumers are invited to talk about a brand, they’re not always going to say nice things.

Marketers refer to this phenomenon as “Hashtag Hijacking”, but that’s a misnomer. Hijacking implies that brands own the hashtag at the start. Unlike traditional marketing messages, brands can’t script the narrative. Brands can spark conversations, but they can’t control them.

A hashtag alone does not make a conversation. They are only a means to an end.

Many marketers assume that consumers are dying to join a brand’s conversations. Instead, consumers have conversations with each other. Brands can be a part of those conversations, but the best examples I’ve seen are when they enable and extend conversations that consumers are already having. My favorite branded example remains Oreo’s 2012 “Daily Twist” campaign. To celebrate 100 years of the Oreo, Oreo posted a new image every day for 100 days, using the Oreo to celebrate different events. It launched with a Gay Pride Oreo, and continued with Shark Week, Mars Rover, Elvis Week, 40 years of Pong, and 95 other images.

With “Daily Twist”, Oreo didn’t merely start brand-centric conversations that consumers could easily ignore. Instead, they inserted themselves in a positive way into conversations that consumers were already having.

In India, the dairy brand Amul has been executing a similar strategy with a weekly cartoon for decades. Each week since 1966, Amul has released a new cartoon on billboards across India that riffs on topical issues, from politics to Bollywood to cricket. The cartoons aren’t about the butter. They’re about conversations that matter to their consumers in India. No wonder this campaign won a Guinness World Record for the longest-running ad campaign in the world.

A hashtag alone does not make a conversation. They are only a means to an end.

.png)

What Did You Think?